Facilitating the Fiscal Contract? The Case of Semi-Autonomous Revenue Authorities in Sub-Saharan Africa

This sub-project comes out of an ongoing PhD, which examines how revenue administrations’ scope of autonomy affects their performance. This PhD project speaks to different literatures on administration and taxation in developing countries, particularly including fiscal contract theory and theory on pockets of effectiveness, as well as the broader public administration literatures on autonomy and performance. The project will include both quantitative cross-country analysis and in-depth case studies of revenue administration in sub-Saharan Africa.

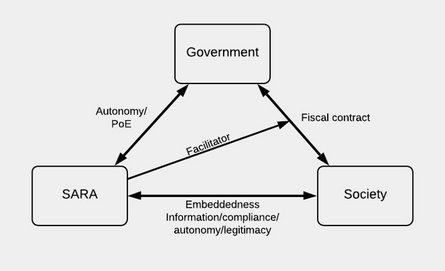

Fiscal contract theory proclaims an interrelationship between taxation and public goods, arguing that states need taxes to function and citizens will demand something in return if required to pay taxes. The micro-foundation of this is the revenue bargains that take place between revenue providers and rulers, but what happens when an intermediate is added to the equation? While the government is in charge of providing public goods to society, many states in sub-Saharan Africa have delegated the task of collecting revenue to semi-autonomous revenue authorities (SARAs). In such, SARAs have been expected to raise revenue and implicitly function as a facilitator of the fiscal contract. Thus, the introduction of SARAs have expanded the stakeholder relationship in the revenue bargaining process from bilateral to triangular adding two new dimensions, which this project will examine.

Extended project description

This sub-project comes out of an ongoing PhD, which examines how revenue administrations’ scope of autonomy affects their performance. This PhD project speaks to different literatures on administration and taxation in developing countries, particularly including fiscal contract theory and theory on pockets of effectiveness, as well as the broader public administration literatures on autonomy and performance. The project will include both quantitative cross-country analysis and in-depth case studies of revenue administration in sub-Saharan Africa.

Fiscal contract theory proclaims an interrelationship between taxation and public goods, arguing that states need taxes to function and citizens will demand something in return if required to pay taxes. The micro-foundation of this is the revenue bargains that take place between revenue providers and rulers, but what happens when an intermediate is added to the equation? While the government is in charge of providing public goods to society, many states in sub-Saharan Africa have delegated the task of collecting revenue to semi-autonomous revenue authorities (SARAs). In such, SARAs have been expected to raise revenue and implicitly function as a facilitator of the fiscal contract. Thus, the introduction of SARAs have expanded the stakeholder relationship in the revenue bargaining process from bilateral to triangular adding two new dimensions, which this project will examine. The figure below depicts this triangular relationship.

The first new dimension is the relationship between the SARA and the revenue rulers in government. To understand a SARA’s ability to bargain over revenue with society (the second new dimension), it is necessary to understand how a SARA bargains with the government over autonomy. While SARAs are often treated as a homogeneous group, their de facto level of autonomy differs and this potentially has implications for how they function. However, autonomy is a rather fuzzy concept. Therefore, to create a meaningful conceptualization of SARAs’ autonomy, it has to be grounded in the reality of revenue administrations in developing countries and the pressures as well as the context within which they function. In this regard, I argue that autonomy is multidimensional; in other words, it is not just a matter of how much autonomy a SARA has, we also need to be aware from whom and to do what. My argument is that the different dimensions of autonomy each have importance for how SARAs perform and how they are perceived by the public. Some SARAs might for example be very autonomous from the government but not from donors. This will arguably influence which tasks they prioritize to focus on. Opposite, less autonomy from politicians might mean more autonomy from multinational companies (MNCs) thus potentially implying that the revenue administration have the needed political backing to make effective revenue bargains with MNCs. Therefore, simplistic understandings of SARAs and their autonomy obscures our understanding of how they functions and perform. This has led to a lack of understanding regarding the effect of implementing a SARA-model and how this affects the revenue authority’s role in facilitating revenue bargains.

The second new dimension is the relationship between the SARA and society. Here SARAs are in a conflictual position; On the one hand, they are assigned with the difficult task of increasing revenue on behalf of the government while, on the other hand, lacking the ability to provide any public goods directly in return to taxpayers in society. So, how can they bargain for revenue? One of the arguments for implementing SARAs was the assumption that increased levels of autonomy would help isolate the revenue administration from undue political interference in the hopes of creating pockets of effectiveness. If this holds true, SARAs’ conflictual position might be eased if they are recognized as fair and unbiased by society and thus perceived as a legitimate authority. But does SARAs level of autonomy influence perceptions of legitimacy? And does this foster taxpayer compliance and mitigate their conflictual position as facilitator of the fiscal contract when bargaining for revenue?

This PhD project will rely on various analytical approaches to answer these questions. Panel data analysis will be used to examine if SARAs in general have lived up to the expectation of increasing revenue, therein setting the stage for examining SARAs’ role more in-depth. Subsequently, to study the importance of autonomy, this project develops a new contextualised concept of autonomy. This concept will be applied in case studies of SARAs, which will also explore if and how autonomy affects perceptions of legitimacy and ease SARAs’ role as facilitator of the fiscal contract.

Figure: The triangular relationship between government, SARA, and society